To Heal Skin, Scientists Invent Living Bioelectronics

Rutgers–New Brunswick engineer and students create patch that combines sensors and bacteria to interact with the body

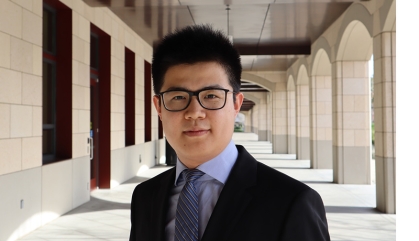

For much of his childhood, Simiao Niu was troubled by psoriasis, a chronic, often painful skin condition, mostly on his arms.

Sometimes, the prescribed ointment worked and treated the inflamed, red areas produced by the disease. But he was never sure if he was using enough, whether the skin irritation was healing and when he should stop treatment.

Years later, as an engineer on the team at Apple Inc. that devised the electronics in Apple watches monitoring heart rhythm, Niu had a revelation: Could a similar wearable electronic device be developed to treat skin ailments such as psoriasis and provide patients with continuous feedback?

Now, Niu, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering in the School of Engineering at Rutgers-New Brunswick, has played a crucial role in the development of the kind of device that he dreamed of: a unique prototype of what he and his research collaborators are calling a “living bioelectronic” designed to treat psoriasis.

Describing the advance in Science magazine, Niu and collaborators, including scientists at the University of Chicago led by Bozhi Tian and Columbia University, reported developing a patch – a combination of advanced electronics, living cells and hydrogel – that is showing efficacy in experiments in mice.

The patch represents not only a potential treatment for psoriasis, but a new technology platform to deliver treatments for medical needs as diverse as wounds and, potentially, various skin cancers, Niu said.

“We were looking for a new type of device that combines sensing and treatment for managing skin inflammation diseases like psoriasis,” Niu said. “We found that by combining living bacteria, flexible electronics and adhesive skin interface materials, we were able to create a new type of device.”

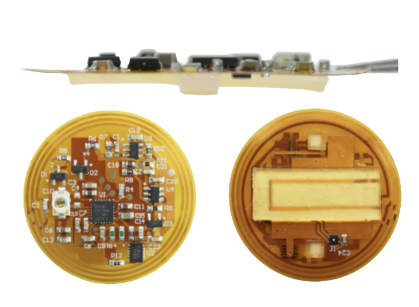

The circular patch is about 1 inch in diameter and wafer thin. The patch contains electronic chips, bacterial cells and a gel made from starch and gelatin. Tests in mice conducted by the research team showed that the device could continuously monitor and improve psoriasis-like symptoms without irritating skin.

The device, Niu said, is a leap forward from conventional bioelectronics, which are generally composed of electronic components that are encased in a soft synthetic layer that reduces irritation when in contact with the body. The electrode patches placed on a patient’s chest for an electrocardiogram are examples of conventional devices.

Niu’s invention could be seen as a “living drug,” he said, in that it incorporates living cells as part of its therapy. S. epidermidis, which lives on human skin and has been shown to reduce inflammation, is incorporated into the device’s gel casing. A thin, flexible printed circuit forms the skeleton of the device.

When the device is placed on skin, the bacteria secrete compounds that reduce inflammation, while sensors in the flexible circuits monitor the skin for signals indicating healing, such as skin impedance, temperature and humidity. The data collected by the circuits is beamed wirelessly to a computer or a cell phone, a process that would allow patients to monitor their healing process.

During his years at Apple, before he joined Rutgers faculty in 2022, Niu and other engineers were forwarded hundreds of thank-you notes that had been sent to the chief executive’s office. The customers wrote to credit their Apple watches with saving their lives, Niu said. The watches’ built-in heart rate monitors pointed to a condition – an arrhythmia known as atrial fibrillation – the customers said they didn’t know they had. Atrial fibrillation can lead to strokes if left untreated.

“When you produce the kinds of things that positively affect people’s lives, you feel very proud,” Niu said. “That is something that inspires me a lot and motivates me to do my current research.”

Clinical trials to test the device on human patients must come next, Niu said, as the first step toward commercialization. Once there is evidence of positive results with minimum side effects, the inventors would apply for FDA approval in order to bring the device to market, Niu said.

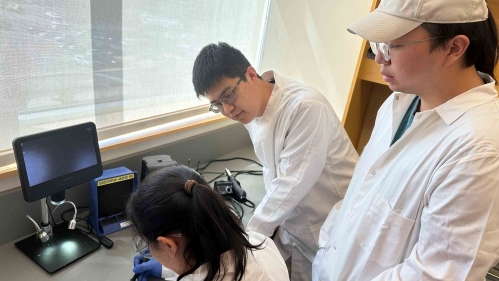

Other authors of the study from Rutgers included Fuying Dong and Chi Han, two graduate students in the Department of Biomedical Engineering in the School of Engineering.